Walter Crane (1845-1915) portrays an immaculately dressed and elegant female kneeling before a statue of the Bard on the frontispiece of Flowers From Shakespeare’s Garden (1906) epitomising for many the quintessential image of the Edwardian lady in the garden. However, her wide-brimmed straw hat, feather boa and long pink dress tell only a partial story. Some women gardeners (as opposed to women in the garden) had already begun by this time to adopt an altogether different attire.

Dog skin and kid gloves had long been worn by Victorian lady gardeners to protect their ‘fingers used to delicate employment’ as they wielded their scaled-down garden spades, forks and trowels. The writer and gardener Jane Loudon (1807-1858) then introduced her gardening gauntlet as a suitable protection for tackling the more robust jobs around the plot.

Meanwhile her fellow writer, Louisa Johnson, advised women gardeners to don “a garden apron, composed of stout Holland, with ample pockets to contain her pruning knife, a small hammer, a ball of string, and a few nails and snippings of cloth.”

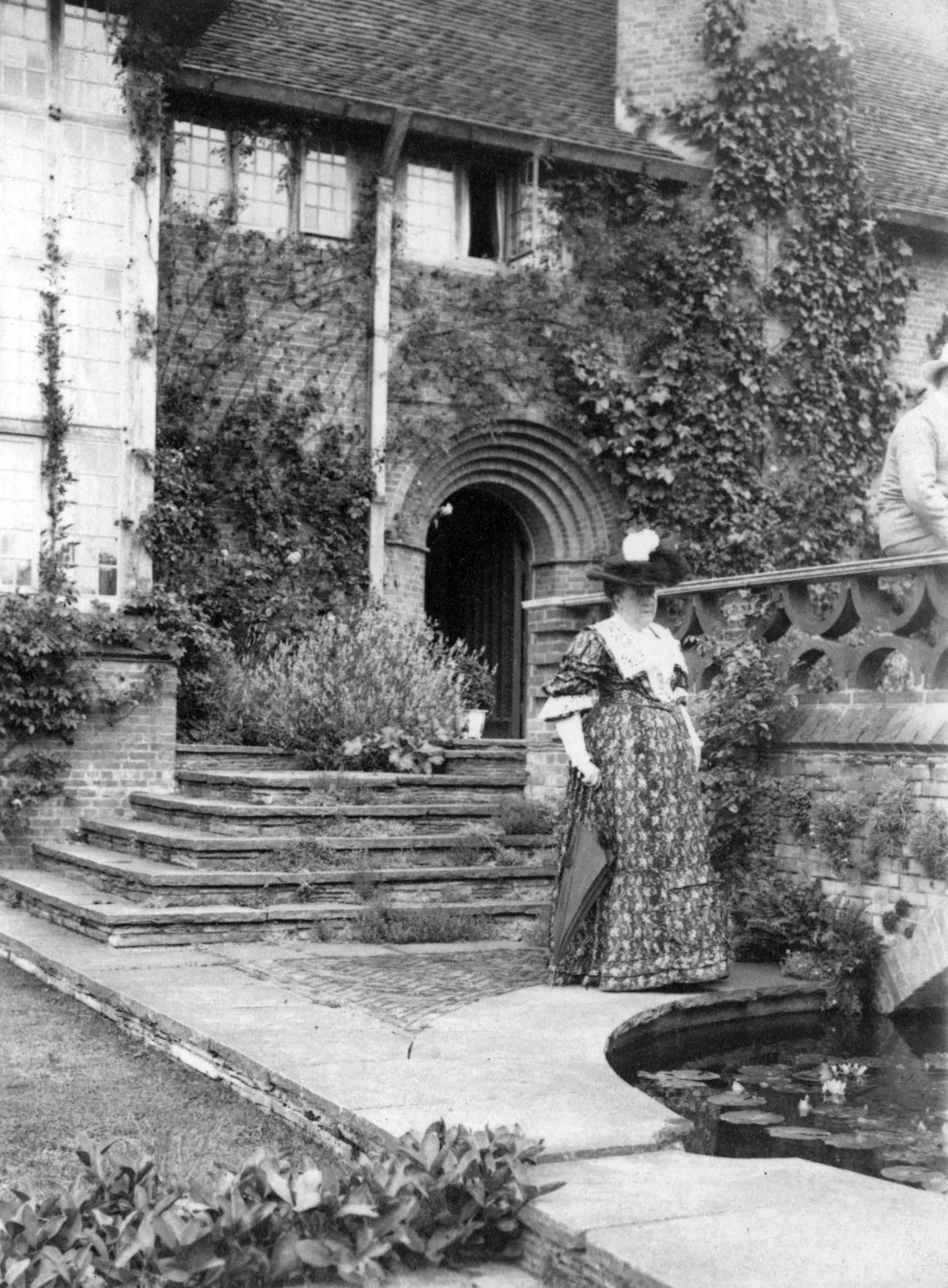

The garden apron, with its capacious pockets, continued to find favour with serious women gardeners. When the young architect Edwin Lutyens (1869-1944) first visited Gertrude Jekyll (1843-1932) at her Munstead House home in Surrey in 1889, he found her dressed all in blue. At this, only their second meeting, she wore a linen apron over her above-the-ankle skirt and box-pleated blouse. The apron’s ample pocket was brimming with gardening tools, ready for action.

Daisy, Countess of Warwick (1861-1938) opened her Lady Warwick Hostel in 1898 – here a more demure look was deemed suitable for its all-female horticultural students. The intriguing and highly original Countess of Warwick was a former mistress to the Prince of Wales turned philanthropic socialist (it is she who fellow socialist sympathiser Crane was to depict so elegantly in Flowers From Shakespeare’s Garden).

Naturally she ensured her students were dressed in a way entirely appropriate to the period. They wore long Edwardian skirts (the hems of which the students often bound with leather – making it easier to clean off mud) along with neat white blouses with a collar and tie. Such restrictive outfits must have made for hot work in the Stove or Melon house! Graceful straw hats added an air of elegance as well as keeping the sun from tanning their fair skin.

The Lady Warwick Hostel, which became Studley Agricultural College for Women in 1910, was only one of the many educational establishments beginning to offer young women horticultural training at this time. The Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew took women trainees from 1896. The Director, Sir William Thistleton-Dyer, deemed that in appearance at least, his new female recruits should resemble their male colleagues as closely as possible.

Thus they wore a masculine-style ensemble of shirt and tie under a heavy brown tweed suit consisting of jacket, waistcoat (complete with watch chain) and a peaked cap. The lower part of the body was clad in the now infamous knickerbockers, which prompted the magazine Fun to pen these lines in 1900:

They gardened in bloomers, the newspapers said; So to Kew without warning all Londoners sped: From the roofs of the ’buses they had a fine view Of the ladies in bloomers who gardened at Kew.

The verse concluded with the refrain ‘Who wants to see blooms now you’ve bloomers at Kew.’ Thistleton-Dyer quickly ordered his students to wear long mackintoshes on their way to work to hide their more contentious items of clothing.

Viscountess Wolseley (1872-1933) was altogether more considerate of both her student’s sensibilities and their comfort when devising an appropriate uniform for her College for Lady Gardeners at Glynde in Sussex. In keeping with the military ethos of the school she founded c1902, Frances Wolseley dressed her young women in a smart uniform of white shirt, khaki-coloured coat and, rather daringly, a mid-calf length skirt. The warm tweed versions were replaced by lightweight linen in the summer months.

When working in the garden the long skirt was abandoned for a more practical shorter one, worn over breeches with boots and gaiters. The rather drab khaki colour was less inclined to show the pale powdery mud of the chalky South Downs soil, than would a more sombre navy or brown.

The students wore a tie in the school colours of red, white and blue, repeated on the twisted cord around their soft felt hats. In her 1908 book Gardening for Women she writes: 'Although a sun-bonnet is very picturesque, it is hot and close, for it keeps off the air as well as the sun. The old-fashioned plan of putting cabbage leaves in the crown of the hat should not be despised, should the heat be felt very much.'

In matters of dress, Wolseley seems always to have had her students’ comfort in mind, rather than any romantic effect a somewhat softer appearance might have created when glimpsed among the sweet peas and roses!

The Glynde students fared far better than their counterparts at Waterperry Horticultural School, Oxfordshire. Beatrix Havergal (1901-80) founded the school with Avice Saunders (1869-1970) in 1927. Their hapless students would appear dressed in breeches, knee-high thick socks, an overall and an unfeminine jacket, all in a less than flattering shade of green. Havagal was certainly no fashion victim herself. Judging from her rather masculine appearance evident in photographs, she was not the kind of woman one would find wearing chic flapper frocks – in or out of the garden.

At the time of the First World War, the fact that women need no longer appear in corseted grandeur when gardening was even being promoted as one of the advantages of a horticultural career. A report entitled ‘The Work of Educated Women in Horticulture and Agriculture’ which appeared in The Journal of the Board of Agriculture in 1915 rather curiously stated the following concerning women engaged in outdoor work: 'they get many of the necessities of life thrown in which in another class on the same income would be regarded as luxuries, such as fresh air, fresh eggs, butter, vegetables and milk and possibly a pony to drive, and they can wear old clothes.' One certainly pities the members of the class who regarded fresh air and old clothes as ‘luxuries’.

The Great War saw the formation of the Women’s Land Army (WLA). With so many male agricultural workers fighting at the front, the sterling work of the WLA was needed to ensure that enough food was produced. Re-formed again during the Second World War, the WLA handbook then expressed concern not just with food production but also with matters of dress and propriety: 'You are doing a man’s work so you are dressed rather like a man: but remember that just because you wear a smock and breeches you should take care to behave like an English girl who expects chivalry and respect from everyone she meets.' A WLA girl could neither wear jewellery nor be seen to put her hands in her pockets.

Vita Sackville-West (1892 -1962) who wrote her propagandist The Women’s Land Army in 1944, seems happy to have adopted a WLA-style uniform of military jodhpurs and boots when gardening at Sissinghurst Castle in Kent. Although her rather aristocratic additions of silk blouse and pearls would certainly have been frowned upon by the authorities.

What then do women wear in the garden today? Well, like high street fashion, it seems that more or less anything goes as long as it is comfortable and practical. Gloves and shoes have always been vital equipment for gardeners, whether male or female. The modish gardener can now have warm, dry, comfortable feet that look good too as stylish French rubber ankle boots (rather endearing named after a spring flower) have replaced the boring black welly.

Gloves can be plain, poker-dot or, like my present pair, patterned with ladybirds. The garden apron is as useful for today’s gardener as it was for Louisa Johnson and Gertrude Jekyll. Choose from heavy duty cotton, suede, tweed or – for luxury and longevity – leather.

The once-ubiquitous waxed jacket is seen less today than it was in the 1980s and 1990s. High-performance, easy-to-wear synthetic fabrics, originally developed for intrepid scalers of mountain tops, can now be seen keeping gardeners warm and dry, while retaining maximum manoeuvrability: a far cry from the heavy tweeds of the ladies at Kew.

So from fine kid gloves and elegant straw hats, to stout aprons, bloomers, sharply cut jodhpurs and chic rubber boots, what women have worn in the garden during the last 150 years has reflected far more than mere changes in fashion. What might often have appeared as little more than modish frippery, actually expressed exactly what type of activity the appropriately dressed lady gardener intended to undertake: be that cutting flowers or digging trenches. Whereas the attire of male and female gardeners today is more or less interchangeable, as indeed, are their activities.