Ceramics run in Kaori Tatebayashi’s blood. Her mother was a ceramic painter in Kyoto and her grandfather, who lived in the famous porcelain town of Arita, in Kyushu, southern Japan, was a tableware merchant. Kaori spent her childhood summers there, hiding in the straw in which the dishes and bowls were packed, hunting for fragments of old Imari ware in the river, and playing in the nearby quarry where the materials for porcelain (kaolin and feldspar) were extracted.

It’s no surprise then that she went on to study the subject but, from an early age, she knew she wanted to do something different with ceramics. “So often ceramics are all about vessels and functional pieces,” she says. “I wanted to see what else I could do.” A Crafts Council touring exhibition of contemporary British ceramics opened her eyes to the possibility of using clay as a sculptural medium and, after a term as an exchange student at the Royal College of Art, Kaori began trying to recreate everyday objects – clothes, hats, shoes – in her favoured medium of stoneware. “It has a warmth that porcelain lacks,” she says, “and I prefer the texture, too.”

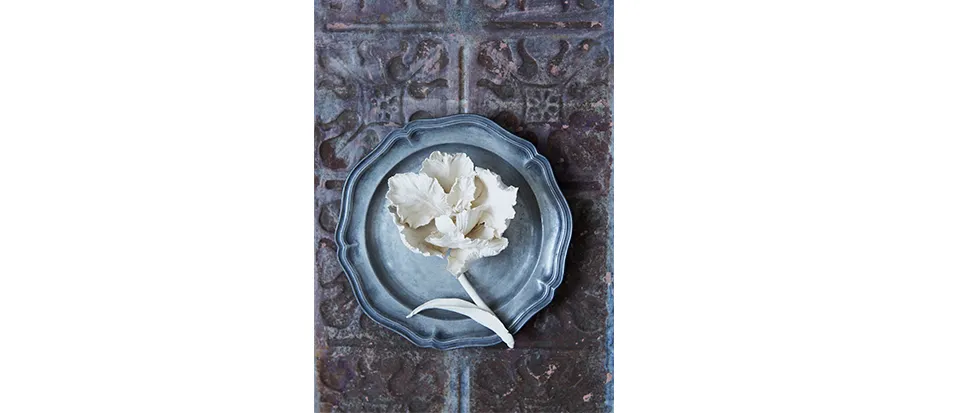

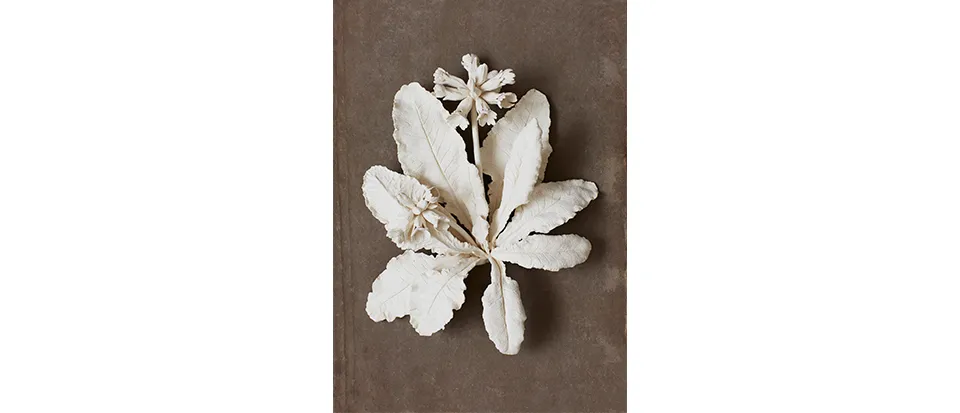

Today, working from her studio in a converted carriageworks in Camberwell, London, it is still this visual sleight of hand that occupies her, although now her gaze has moved on to plants. “As I developed my work, I always had a strong sense that the organic life of the clay stopped with its firing,” she says. “After firing, my pieces become like ghosts, frozen in a moment and yet simultaneously everlasting, so long as you don’t break them. I realised that by modelling things that had been alive to begin with – plants, flowers and insects – I would get a much stronger sense of time being suspended.”

Kaori often wishes she could freeze time during the making of her pieces, too. Always working directly from life, she has but a few short weeks a year to capture those blooms she wishes to make – a solo show at Tristan Hoare gallery in London in May this year meant she missed the flowering of Fritillaria persica, which will now have to wait another year. Though she relishes a challenge – the pinked edges of melianthus leaves and the unbending solidity (quite at odds with the properties of the clay) of a magnolia branch being two of the most recent – there are some flowers she won’t even consider attempting. “Umbellifers just don’t work,” she says, “and bluebells are very tricky, too. The pedicels that attach the flowers to the stem are too fine.”

Her challenge lies not only in “extracting the essence from each flower”, as she puts it, but in making them in a way that will survive the firing process, as well as transport and installation. To that end, she constructs her pieces directly on a kiln shelf, working fast so that the clay does not dry out, often making them in segments for assembly directly on the wall.

“I always like to visit the place where my work will hang,” says Kaori, who now works mainly to commission, crafting plants from clients’ gardens or flowers that have special significance to them. “The space around my sculptures is as important as the work itself.” Asked whether she could ever envisage switching subjects, she demurs. “Even if I’ve made a flower before, each time it still really excites me. As long as that continues to happen, I think I’ll stick with this.”

USEFUL INFORMATION

Find out more about Kaori’s work at kaoriceramics.com