IN BRIEF

What Private garden on the edge of Lake Wingecarribee near Burrawang Where New South Wales, Australia Size Five acres Soil Basalt loam Climate Subtropical, with hot summers and mild winters Hardiness zone USDA 9.

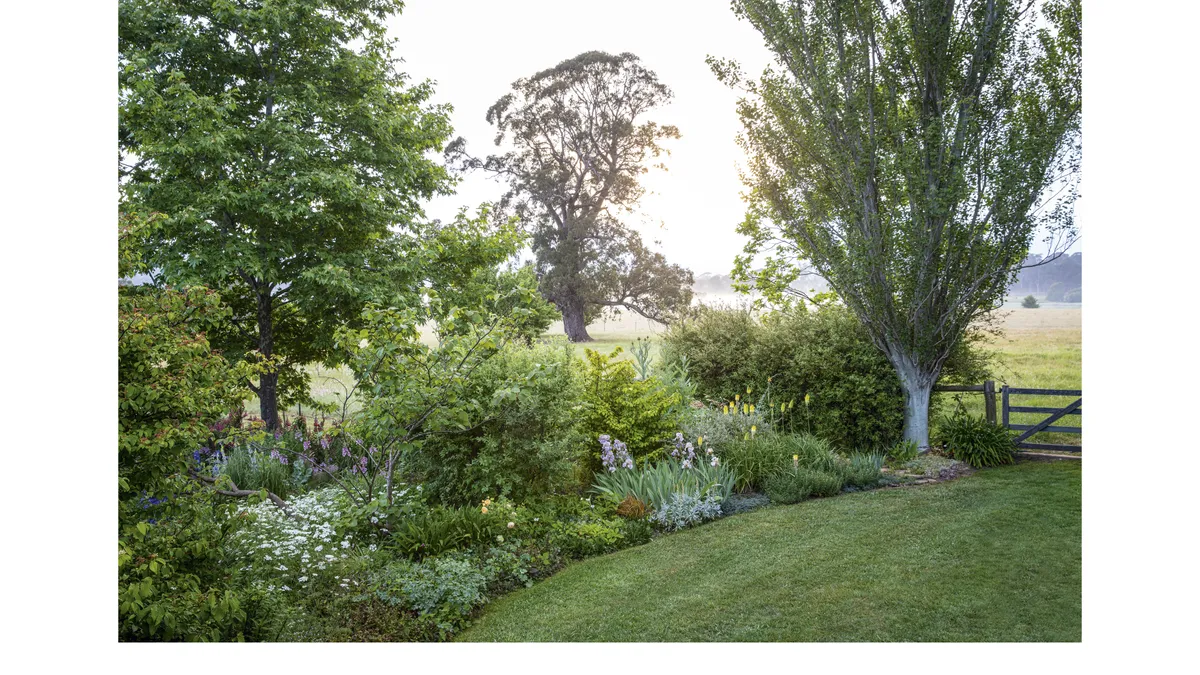

If you have ever wondered why everyone seems to be doing prairie-style gardens except you, don’t worry – there are people who are thinking the same thing in Australia too. In the Southern Highlands of New South Wales, Colin Blanch has made an ‘English’ garden for his clients, with colourful borders cutting across lawns and well-placed trees leading the eye to the rolling hills beyond. Suffolk sheep are often part of the picture, roaming past the lake. With hundreds of acres of pasture beyond an informal yet highly tuned garden, the scene here is more ‘cottage gentry’ (to use Christopher Lloyd’s term) than humble cottage, but English it seems to be, with a cool climate to help.

The altitude here is equivalent to that in parts of the Pennines. There is high annual rainfall, but otherwise this area around Burrawang (an hour from Sydney) has with its “lovely, long summers” a distinct edge on Britain’s climate. Temperatures from December to February average 26-28°C, with only a few uncomfortably hot days. Even the winters are pleasant, the days beginning with frost followed by sunshine and warmth at 18-20°C, and the garden’s north-facing orientation means that it is blessed with “amazing light”.

The planting

Colin is a regular at the iconic English garden that is Great Dixter, crossing the globe for an annual recharge that involves symposia and volunteering. He is also an impressive fund-raiser for the East Sussex garden, finding no shortage of Dixter fans in his corner of southeastern Australia. The British horticultural influence is uncomplicated, he says: “A lot of us are colonials who emigrated here years ago.” He is less interested in bringing native plants into the garden than coaxing later arrivals: “We want things in the English style because it’s a challenge to grow them,” he says. And, most importantly, the cottage lexicon of lupins, delphiniums and foxgloves is preferred.

Traditional plants are not incompatible with the legacy of Christopher Lloyd and the spirit of Great Dixter. Colin’s mentor, Dixter’s current head gardener Fergus Garrett, has said that he looks at a plant’s qualities and what they might bring to a garden, irrespective of prevailing opinions. “The prairie-style movement is of the moment. Cottage (or English-style) gardens have been pushed into a corner,” says Colin. “I don’t want to jump on the trends.” Instead, Colin and the garden’s owners are interested in a blooming garden, with flowers to cut.

Some of these cottage staples need extra attention in New South Wales. Delphiniums and lupins are grown as annuals, for instance. “With our long summers they get tired later in the season,” says Colin. “Some hang in there for a few years, but it’s easier to start afresh with new ones.” The key to cutting without ruining the garden picture is abundance: “I’ve always put lots in,” says Colin. “People should be able to gather a lot of flowers; we are probably inside more than we’re outside.” Mass planting also reduces the impact of snail damage. Other pests include cockatoos and rabbits, which are generally kept away with fencing that is buried half a metre down.

Colour is paramount, and this includes lashings of white. “I love white in a garden but I don’t want an all-white garden,” says Colin. “White is a good colour breaker if you are using harsh colours.” The word ‘harsh’ indicates solid shots of yellow, red and bright blue. He uses white as a conduit between the azure of Delphinium ‘Guardian Blue’ and royal-purple Delphinium King Arthur Group, with an undercarriage of harmonising Nepeta racemosa ‘Walker’s Low’. White Lupinus ‘Noble Maiden’ is a motif around the garden, separated from the raspberry shades of Lupinus Band of Nobles Series by self-seeded foxgloves

Different textures of white are put together: large and small umbels of Orlaya grandiflora with Ammi majus draw attention not only to their structural differences but the green textures around them, such as leaves and young seedheads of opium poppies. Earlier-flowering shrubs Viburnum plicatum f. tomentosum ‘Mariesii’, Exochorda x macrantha and Spiraea cantoniensis make a backdrop of complementary sprays of white blossom, for a border of emerging Kniphofia ‘Limelight’ and common flag iris.

In the curved border farthest from the house, lawn and landscape are separated with mounds that resemble evergreen topiary but are in fact perennials Aster x frikartii ‘Mönch’ and Hylotelephium ‘Herbstfreude’, the latter growing happily up to a metre high, “with rich, pink heads in summer”. Before that, Digitalis purpurea f. albiflora adds movement to the Miscanthus transmorrisonensis that interacts with the shapes of the landscape. Colin insists that his Australian-English garden is no more labour-intensive than a European-American prairie garden: “To me, the maintenance is similar,” he says, speaking over a chorus of brown marsh frogs in full song. “It’s not a chore, it’s creating – and that brings me a lot of happiness.