With the announcement that Munstead Wood has been purchased by the National Trust, we look back at the remarkable life of one of horticulture's enduring legends.

Discover the legacy of Gertrude Jekyll

Which gardener, more than any other, has had the most enduring influence on the British garden? For me, standing head and shoulders above the rest, is the paradoxically short, stout, bespectacled form of Gertrude Jekyll. Although it is 91 years since she died, her ideas about colour, harmony, rhythm; about the grouping of plants and the organisation of the garden (gradually relaxing into wildness as we move further from the house) continue to underpin 21st-century thinking. Only now are Jekyll’s flowing drifts giving way to naturalistic matrices of planting. But balancing a satisfying formal structure with loose, richly textured planting, remains, for many of us, the goal we long to achieve.

The historian Catherine Harwood has described her as ‘the Queen Victoria of horticulture,’ yet Jekyll was by no means a typical Victorian lady, being unusually well educated and well travelled; independent in both mind and means, and resolutely single. She was one of the first women in Britain to train as an art student, and became a highly accomplished textile artist, as well as painting, making furniture, pots and metalwork. Her study of the vernacular architecture of Surrey would inform not only her new home at Munstead Wood, but the gardens she would create with the architect she engaged, one Edwin Lutyens.

She met Lutyens over tea with a neighbouring rhododendron fancier (a common affliction in Victorian Surrey). On the face of it, it seems an unlikely friendship, between the untried young architect and this rather formidable middle-aged spinster. Famously, Jekyll came late to gardening, claiming to have turned to the soil only when her eyesight failed. ‘When I was young I was hoping to be a painter, but to my lifelong regret I was obliged to abandon all hope of this... on account of my extreme and always progressive myopia.’

But being forced to look at things close-to fostered a minute exactness of observation, which was her gift (along with her enviable address book) to the young man. It was this fine appreciation not just of nuances of colour, but of texture and form, that made her so outstandingly successful at placing and combining plants in the border.

To Lutyens she became a kindly mentor, known affectionately as ‘Aunt Bumps’. Together, they made over 100 gardens – less than a third of Jekyll’s prodigious output, but justly legendary. They created complex, romantic spaces we still admire today.

When Lutyens and Jekyll began their collaboration, the gardening world was in a state of war. On one side stood Jekyll’s old friend William Robinson, champion of the wild garden, impassioned enemy of all things clipped, terraced and formal. On the other stood John Sedding and Reginald Blomfield, who held that a garden should be an extension of the house, governed by principles of architecture rather than horticulture. A bitter war of words continued throughout the 1890s, forcing the combatants into extreme positions somewhat removed from their actual gardening practice. Jekyll was vastly amused to discover that Robinson’s garden at Gravetye contained an area ‘all in squares’ while Blomfield had a garden on a cliff ‘with ne’er a straight line in it’.

Into this stormy sea floated the serene gardens of Jekyll and Lutyens, a sublime synthesis in which the loose, informal planting beloved of Robinson was displayed within a tight geometric framework. An understanding of the possibilities of plants and respect for place combined in gardens many believe have never been surpassed.

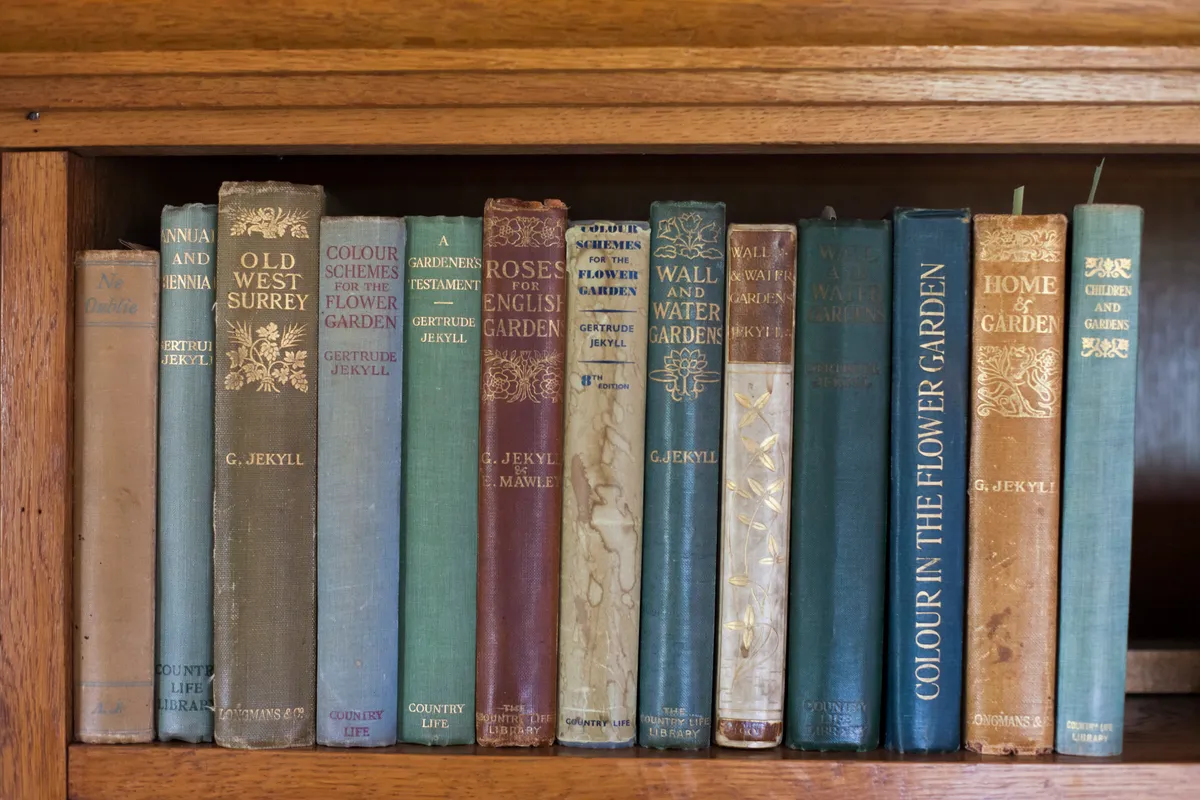

Perhaps Jekyll’s greatest insight was how our perceptions, and indeed our emotions, can be manipulated by juxtapositions of colour. As a student, she had spent long hours copying Turners, and it is thought that his painting The Fighting Temeraire may have suggested the colour sequence for her great border at Munstead Wood. Certainly there are tricks here that Jekyll copied: yellow fading to white to create an aerial quality, while purples, silvers and blues are used to suggest distance. Writing about this border in Colour in the Flower Garden (available today as Colour Schemes for the Flower Garden), she describes how one colour flows into another, from cool to hot and back again. She notes how the border works as a whole, but also how each portion ‘becomes a picture in itself’ and stimulates an appetite for the colours which follow.

She taught us to look at the garden in a painterly way: ‘I am strongly of the opinion that the possession of a quantity of plants, however good the plants may be themselves and however ample their number, does not make a garden; it only makes a collection.’ She thought of her plants as ‘paints set out upon a palette’, and our job as gardeners ‘so to use the plants that they shall form beautiful pictures’.

While believing that gardening ‘may rightly claim to rank as a fine art’, her approach was unwaveringly practical: she made her living by selling plants to her clients, and never recommended any plant or idea she had not first tried out herself. She drew no distinction between fine art and craft. ‘To plant and maintain a flower border, with a good scheme for colour,’ she writes, ‘is by no means the easy thing that is commonly supposed.’ The ‘maintain’ is important: it is typical of Jekyll that she acknowledges the craft and the graft.

Her joy was to be in ‘closest acquaintance and sympathy with the growing things’; her aim, to make of the garden ‘a place of perfect rest and refreshment of mind and body.’ Here, surely, is a vision of gardening that will never go out of fashion.

Timeline of Gertrude Jekyll's life

1843 Born in London, 29 November.

1861-63 Studies at South Kensington School of Art, followed by travels in the Mediterranean.

1869 Meets William Morris and becomes a devotee of the Arts and Crafts movement.

1881 Jekyll’s first articles appear in William Robinson’s The Garden magazine. Asked to advise on Oaklands (now RHS Wisley).

1882 Buys 15 acres of heath and woodland. Begins Munstead Wood.

1889 Over tea with her neighbour, Henry Mangles, meets a young architect, Edwin Lutyens.

1891 Advised by a leading oculist to give up painting and embroidery. She helps Lutyens with his first commission; he begins work on a garden retreat for her.

1897 Moves into new Lutyens house at Munstead Wood.

1899 Publishes her first book, aged 56 – Wood and Garden, followed a year later by Home and Garden. More follow including the seminal Colour in the Flower Garden and Gardens for Small Country Houses.

1901-02 Creates influential Deanery garden for Edward Hudson.

1903 Jekyll and Lutyens begin work on Hestercombe, considered by many their masterwork.

1906-12 Works on Folly Farm, Berkshire.

1918-32 Jekyll continues to work on over 300 planting plans, rarely leaving Munstead as her sight deteriorates.

1932 Dies 8 December at Munstead Wood. Lutyens designs her memorial, inscribed ARTIST, GARDENER, CRAFTSWOMAN.